investment viewpoints

Pandemic impact on credit: default risk

The COVID-19 pandemic spurred a selloff of corporate bond markets in Spring 2020 that brought higher yields back into the fray as it raised concern about default risks from the sudden economic shutdown.

Global policymakers unveiled unprecedented stimulus – both fiscal and monetary – to address the effects of the pandemic and ease systemic risks. Such monetary accommodation is already strongly supporting credit spreads and more fluid credit market conditions, and will likely continue do so until the COVID-19 economic shock has eased, in our opinion.

In the past, credit spreads have generally tended to over-estimate default risks, and we point to past evidence that shows issuers tend to consistently default at a much lower rate than what is priced by the market. In addition, default risk is not spread evenly across the ratings spectrum, compositional effects are significant and there is a significant risk-premium in the BB bucket relative to historical default probabilities.

As such, credit spreads in crossover ratings – BBB to BB – more than compensate investors for the default risk, in our opinion. There are clear openings in credit markets for specialised, active managers to deliver alpha, while long-term investors could finally resolve the low yield conundrum of recent years. Our crossover strategy focuses on quality, aiming to generate higher risk-adjusted return potential compared to traditional investment grade benchmarks.

Credit spreads tend to overestimate default risks

As credit spreads have widened significantly in Spring 2020, it is important to remember that credit is a mean-reverting asset (in the absence of defaults) through the pull-to-par effect.

A long-term buy-and-hold investor would receive the spread of a bond to compensate for future defaults. Historically, credit spreads have significantly overestimated defaults. The excess spread over future defaults, also called the credit spread premium, has reached highs in times of credit distress. Multiple academic studies attribute a large chunk of this credit spread premium to a combination of liquidity1 and jump-risk premium2.

Jump-to-default events, however, appear to be relatively rare for viable non-financial corporates, even during times of stress because, often, the banking sector as well as governments tend to be a backstop if the business is deemed viable3. Indeed, we see this dynamic in play from the very strong fiscal and monetary support provided during the current crisis.

Our empirical analysis shows that outside of accounting scandals,4 investment grade or even highly rated high yield (BB ratings) issuers tend to consistently default at a much lower rate than is priced by the market.

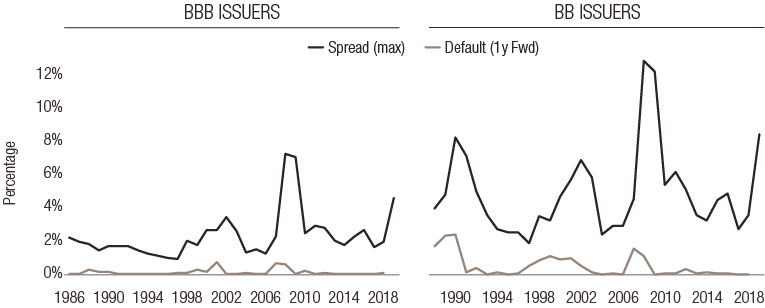

In Figure 1 we plot maximum spreads each year against 1-year forward default losses from Moody’s for the BBB and BB universe. Spreads – which should normally compensate for defaults – have exceeded future default losses by as much as 10x in crisis periods. The maximum annual 1-year default losses5 has been in the range of 0.6% for BBB6 and 1.5% for BB issuers. Credit spreads however reached 7% and 12% respectively in the 2008 financial crisis and 4.5% and 8% in the current crisis.

Figure 1. Spreads (max annual) vs 1-year forward defaults

In the current crisis, US credit spreads hit their highest since the 2008 crisis, and EUR spreads are just below the peak hit during the Eurozone sovereign crisis.

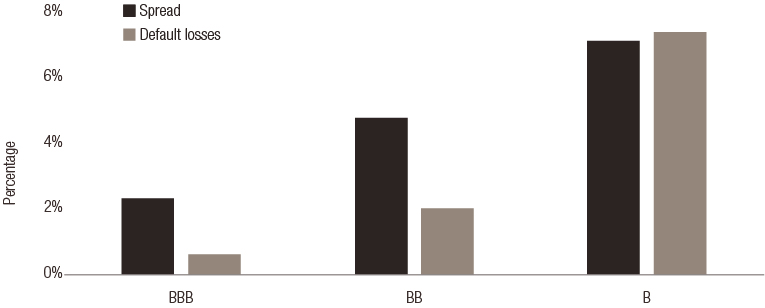

As an anchoring exercise, Figure 2 compares current spreads with the highest average default losses over the past 40 years7. Current spreads are almost 4x the historical worst-case defaults in BBBs and almost 2.5x historical worst-case defaults in BBs. In contrast, lower-rated HY issuers such as Bs have spreads that are in line with worst-case defaults.

Figure 2. Spreads at 29 May 2020 vs maximum historical default losses

Calibrating the current default cycle

Defaults are expected to be substantially higher in the wake of the sudden economic shutdown. However, unprecedented government support should help mitigate defaults, and we believe impacts will vary.

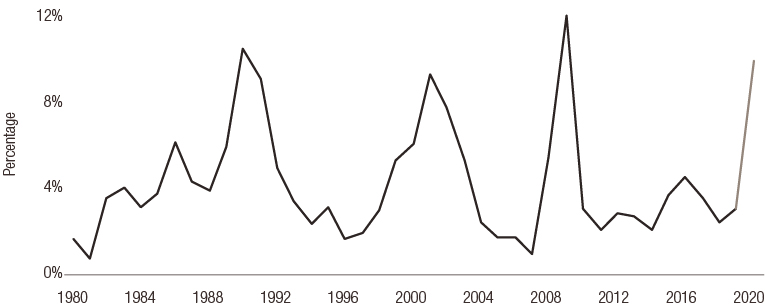

Rating agency and broker research estimate issuer-weighted speculative-grade default rate of 10%8, almost 3x pre-COVID crisis levels, and only rivalled by the 2008 crisis, as shown in Figure 3. However, we think that even at these stressed default levels, credit spreads more than compensate for defaults within standard bond indices.

Figure 3. Global Moody’s speculative grade defaults

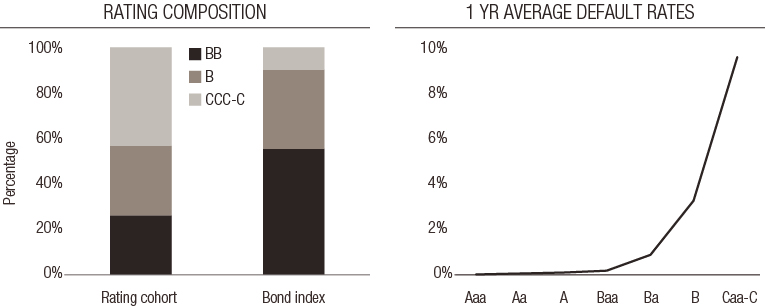

It is important to note that speculative grade default estimates are not comparable historically or with standard bond indices because of composition effects. Rating agency cohorts are dominated by CCC-C rated issuers from the proliferation of smaller companies raising funding from public markets. Bond indices, such as the Bloomberg Barclays high-yield corporate index, have a very different composition. This is both from differences in the issuer mix as well as the weighting scheme.

For example, Bloomberg Barclays indices have a USD 150M outstanding constraint for high-yield issuers that eliminates many small companies that are low-rated. In addition a large proportion of very low rated issuers (B- and below) are private equity owned companies that are financed by bank loans9. Finally, market-cap weighting also reduces the CCC-C rated exposure as BB-rated companies are substantially larger.

Panel A of Figure 4 shows that high-yield bond indices are dominated by BB issuance which constitutes ~ 55%, and B constituting 35%. Panel B shows that the default rates increase exponentially10 when moving down the credit spectrum, therefore composition effects can be very significant.

Figure 4. Rating composition and default rates by rating

Source: Moody’s, Bloomberg Barclays indices.

Source: Moody’s, Bloomberg Barclays indices.Please click here to download the full white paper entitled ‘Credit where credit is due.’