investment viewpoints

Five reasons why the oil shock and COVID-19 may be positive for climate investment

In the global COVID-19 pandemic countries are working to strike a balance between protecting health, preventing economic and social disruption, and respecting human rights. The pandemic is first and foremost a humanitarian tragedy but is now severely impacting on the global economy and has become intertwined with an oil price collapse and market turbulence across asset classes.

There are five key reasons why we believe the oil price shock may well accelerate the transition to a net-zero economy:

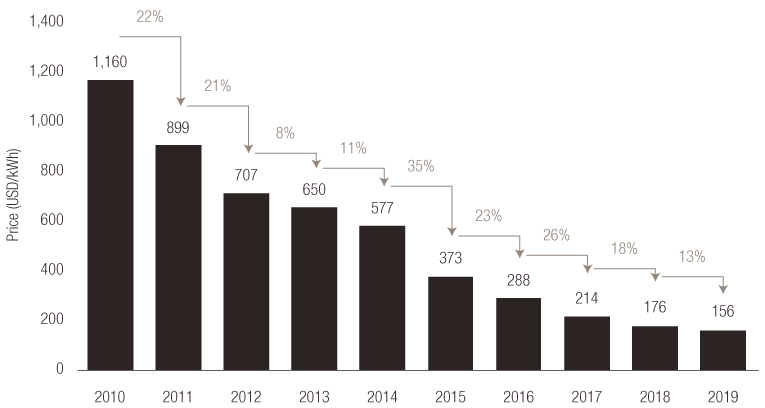

Battery cell prices have fallen 87% since 2010

Source: BNEF

sources.